Be a Great Rejector

What deer, cheetah, bumblebee, and dodo can teach us about investing

NOTES

Md Nazmus Sakib

11/15/20243 min read

When a deer sees a watering hole, it doesn’t always run toward it to quench thirst even if the watering hole seems safe. The deer knows that the cost of missing out on the easy source of water is less than the cost of a predator’s ambush. Not taking action leads to errors of omission (the deer going thirsty for some time), but saves it from extinction.

A cheetah is the fastest mammal on Earth but lacks in size and strength compared to many other competing predators. It doesn’t attempt to kill an adult water buffalo, a favorite prey of lions. Doing so would lead the cheetah to commit errors of commission by choosing the wrong prey. It preys on smaller animals like rabbits and small antelopes. Sometimes a cheetah doesn’t chase an animal that it should have. It leaves the family hungry for a while by being selective they get to see another day.

The flightless dodo birds, a native of Mauritius, were first spotted by sailors in 1507 and went extinct by 1681. The cause of the extinction? Dodo made lots of errors of commission. Dodos didn’t face natural predators on the isolated island until humans invaded. The birds didn’t avoid humans or other animals they brought with them as they (dodo) were unaware of the risk. Dodos roamed around freely and fell prey to risks they never faced before.

Bumblebees have been around for about thirty million years. Their predators are crab spiders and birds. In an experiment, scientists created a garden of artificial flowers that also contained some robotic crab spiders. They hid some spiders and made others visible. Whenever a bumblebee landed on a flower with a crab spider, the spider captured the bumblebee between its foam pincers. Within few seconds, the robotic spider released the bee. Soon, the bumblebees started committing errors of omission. They started avoiding flowers even where there were no spiders.

All these stories teach us that the species that survived for long were very sensitive to errors of commission. The instinct of avoiding errors of commission at the expense of errors of omission, which means to be okay with missing out on some opportunities, have helped some species survive for millions of years while the absence of this instinct caused some species go extinct.

The lesson from this rule of the natural world is to avoid big risks. Optimise for making less errors of commission at the expense of more errors of omission.

Warren Buffett laid out these two rules of investing long before: never lose money, and don’t forget to never lose money. A great investor is a great rejector as well. The author of the book ‘What I learned about Investing from Darwin’, who is also a successful fund manager, forgoes potentially juicy opportunities if the risk of losing capital is high.

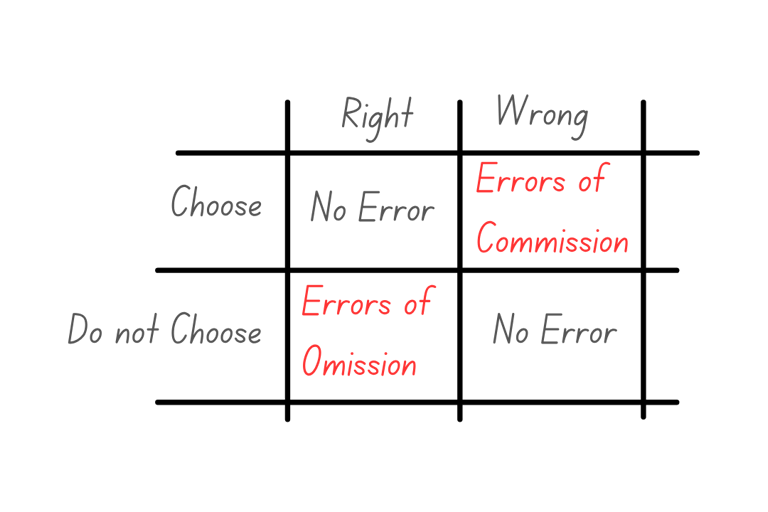

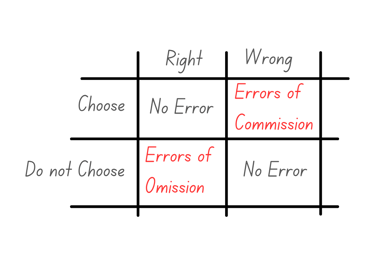

In investing, errors of commission happen when you choose the wrong investment and errors of omission happen when you do not choose the right investment.

Chasing too many opportunities can lead to fatal mistakes (errors of commission). You have to make a trade-off. If you want to limit errors of commission, you will have to commit many errors of omission. Most successful investors only bet on few things where they have some sort of edge (e.g. informational or analytical edge) and avoid most of the trends that the market is euphoric about. They don’t play the game beyond their circle of competence. They are great rejectors. They know that the trade off between errors of commission and errors of omission is not symmetric. If an investor tries to catch up on every opportunity, he or she is most likely to commit errors of commission. Yes, he will occasionally win few rounds, but as natural world teaches us, when he makes an error of commission, it poses a threat to his survival.